Adi Weidenfeld,

Faculty of Economic Sciences and Centre of Excellence in Social Sciences

University of Warsaw, Dobra 56/66 St. Room. 2.90

00-312 Warsaw, University of Warsaw, ul. Długa 44/50, 00-241 Warsaw, Poland

a.weidenfeld@uw.edu.pl

Nick Clifton

Department of Accounting, Economics and Finance,

Cardiff Metropolitan University, Cardiff, UK CF5 2YB

nclifton@cardiffmet.ac.uk

About a report:

Transnational municipal networks, are cities working together across borders have been growing fast. But with that growth, some participants feel like decisions about who joins are made without enough input, leading to weak commitment and wasted time and money. Our study took a fresh look at existing data and suggests that these networks don’t just run based on their rules or the people involved—they’re also shaped by qualities like how connected they are, how clearly defined their goals are, and how focused their efforts are. These qualities can shift over time. By looking at things from a network and systems point of view, the paper helps us better understand how these city partnerships work and how to make them more effective. It also offers a framework, with real-world examples, to show how these kinds of international city networks evolve.

How Transnational Municipal Networks Have Grown and Changed

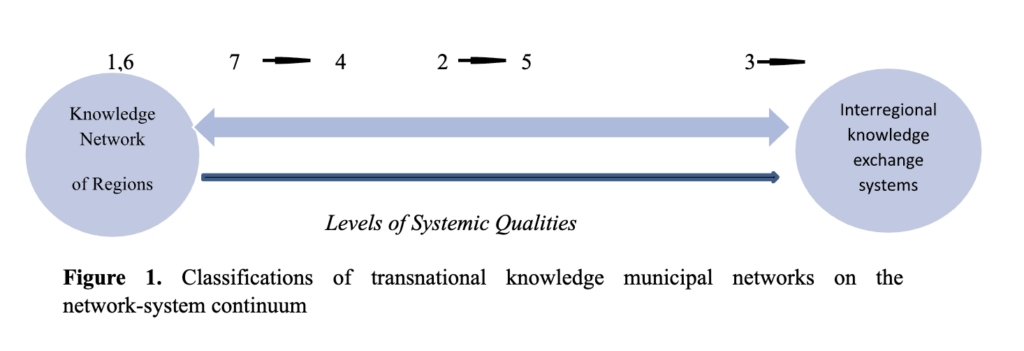

Our study looks at how four of the older cross-city networks (the ones that have been around for over five years) have either stayed the same or evolved. Think of it like checking whether they’ve grown tighter and more connected or stayed scattered and loosely organized. The changes are shown in Figure 1 using arrows, which track how their setups have shifted—some becoming more structured, others less so. After that, it takes a quick look at three newer networks (networks 5 to 7), though there’s less data available for those.

- Districts of Creativity Network (DC Network): This network started back in 2004 as a political effort, but over the years it’s turned into something more practical and idea-driven. What began as a regional project now has global ties, with a focus on hot topics like digital tech and sustainability. Its main strength is pushing creative thinking across different fields to support economic change and entrepreneurial energy. Members come from all over—regions, states, and even autonomous nations—with all kinds of organizations getting involved, from government bodies to research institutes. That said, the network hasn’t really settled into a unified or tight-knit system. It allows members to explore lots of different themes and approaches, which keeps things flexible but also means they’re not working toward shared goals. Because of that, its ability to actually share knowledge and drive change across the whole network is pretty limited. It’s a good example of a loose, non-mission-focused group—great for individual creativity, but not super effective as a coordinated force.

- Global Resilient Cities Network (GRCN): Launched in 2013 with backing from the Rockefeller Foundation, this network was built to help cities deal with big global problems: rapid urban growth, globalization, and climate change. At first, each city had a Chief Resilience Officer to lead the charge, and over time the effort expanded to include more hands-on roles, connecting public and private partners, and inviting all kinds of cities to join in. This network is part of a newer trend where public, private, and non-profit sectors mix to push bold climate action. Sponsors have played a big role, not just by funding but also by setting the direction and even removing cities that didn’t keep up. As a result, more cities have come on board—as long as they’re on the same page about climate goals. What makes this network interesting is how it moved from being a donor-funded project to a city-led community tackling a variety of resilience challenges. Cities also seem to connect better when they have similar political or regional setups, and there’s been real sharing of ideas and practices. Compared to the previous network, this one sits more in the middle when it comes to being organized and goal-oriented. It’s not fully locked in, but it’s moving that way—welcoming a broader range of cities and perspectives, which can actually help it grow stronger and more efficient over time.

- C40 Cities :C40 started out as a small group of major cities but has grown into a heavyweight global network influencing climate policy. Today, it represents cities home to 650 million people and a quarter of the world’s GDP. It went from simply swapping ideas to becoming a leader in climate advocacy, especially focused on fairness and resilience. Only the world’s biggest and most committed cities can join—there’s a pretty high bar. It’s seen as a sort of “elite club” with strong organization and internal structure. Formal rules guide how members behave, but behind the scenes, there’s also a lot of trust-building and informal teamwork. C40 stands out for helping cities shape serious climate goals, share smart solutions, and learn from one another. It even runs a central “knowledge hub” that city officials tap into for tips and tools.While it started off pretty exclusive, it’s become more regionally balanced, hiring local leaders in different areas. There’s still strong backing from private groups, creating a mix of public and private decision-making. Thanks to all this, C40 has stayed consistent and highly coordinated—but as it grows, it’s split into smaller topic-based groups. The big question is whether it can stay united as one big network or if it’ll eventually evolve into several smaller ones.

- International Urban and Regional Cooperation (IURC) This group launched in 2016 and started out mainly for European cities. But in 2020, it threw open the doors to cities and regions around the world. That helped bring a bit more unity, even though cities differ a lot in terms of size, budget, and ability to get things done. Its main way of working is pairing up two cities, but those differences sometimes make teamwork hard. So while it’s becoming a more open, inclusive network, it’s not yet functioning smoothly as a cohesive system. Unless it gets clearer focus or tighter partnerships, it might just remain a loose collection of city pairs rather than a powerful force.

- Partnership for Healthy Cities: This one’s all about improving health in cities—think anti-smoking laws or healthier public spaces. It started with a small, handpicked group of mayors (max four per country!) and aimed to achieve quick wins to build momentum. Since 2019, it’s grown and relaxed the rules a bit, letting in more cities and allowing more flexibility in what health issues they focus on. Private backers play a major role here, especially in cities from lower-income countries. It’s a pretty organized setup with strong potential, but right now there’s not much collaboration between members. If cities begin working together more and combining their know-how, the network could become a real powerhouse.

- Mastercard City Possible : This network is powered by—yep, Mastercard. It brings cities, businesses, academics, and communities together to tackle shared urban problems, especially using tech. It’s open to anyone, so it grew fast, boasting over 220 cities by 2020. But here’s the thing: there’s not much evidence that it’s working as a connected system. It’s got some structure, but no real sense of direction or teamwork yet. At this point, it’s more of a platform with potential than a strong, evolving network.

- ASEAN Smart Cities Network: This is a newer network driven by the Singaporean government and some private partners, with a focus on Southeast Asia—though others are starting to join. It’s still early days, and there’s more informal collaboration than formal rules. Cities share ideas on how to improve urban life using tech and smart planning. Each city designs its own action plan tailored to local needs. Lately, there’s been an effort to build stronger systems and formal processes, especially through regional partnerships. That’s helping the network grow more cohesive and capable over time. While it’s still on the less-developed end of the spectrum, it’s slowly becoming more connected and structured. If it keeps pulling in more diverse partners and coordinating better, it could turn into something much stronger.

Practical implications/recommendations

Choose the right network for your city – When considering joining a transnational municipal knowledge network (TMKN), select one that matches your city’s challenges, location and governance style. Focus on networks where existing members have expertise that will be most valuable to your city’s needs.

Summary

Our study looks at how international city networks, called Transnational Municipal Knowledge Networks (TMKNs), help their members share knowledge and drive innovation. It focuses on how these networks are set up, how they grow and change over time, and what makes them work well.

By analyzing seven examples of these networks, the authors explore what factors—like governance, funding, and how members are selected—affect their success. They argue that TMKNs work best when they have strong internal systems and shared goals among members. But these conditions can shift as the network evolves.

We highlight that networks with closer geographic or cultural ties may work better together. Our study raises the importance of both setting clear missions and having the right infrastructure to support innovation, especially across different regions. Finally, we call for more detailed research using interviews and case studies to better understand how these networks function and how they can improve.